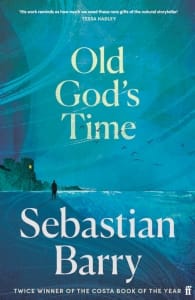

Old God’s Time

Reviewed by Wendy Tucker

Reviewed by Wendy Tucker

Sebastian Barry

Old gods’ time is ‘an expression indicating a period beyond memory’ and also applies to a memory from so long ago that it belongs in the time of the old gods, such as those of the Greeks. It is the perfect title for this novel that is all about the struggle with memory, what is real, what is imagined and what is too traumatic, too damaging to be allowed to surface.

This is the eleventh novel of Sebastian Barry, an acclaimed Irish novelist, playwright and poet. And he is still taking risks with prose, structure and subject.

The novel is written in the third person but we, the readers, are entirely in the head of Tom Kettle who is protagonist and narrator.

Tom Kettle is nine months into retirement from the Garda, the Irish police. He now lives in a small, badly-built addition attached to a Victorian castle but now divided into flats with his the least attractive. The setting is Dalkry, on the wild Irish coast, an hour from Dublin surrounded by garden and sea that makes up for the dreary accommodation. ‘… he was quite content to just gaze out. Just do that. To him this was the whole point of retirement, of existence – to be stationary, happy and useless.’

But Tom is not happy, memories intrude and Tom is ‘the orphan of his former happiness’.

Some things slowly become clear. Firstly Tom’s overpowering, overwhelming and everlasting love for his dead wife, June, his love, respect and empathy for all humanity, and his belief in justice and a personal moral code. The second is that Tom’s memory is unreliable. He is a grief-stricken witness to a life of multiple disasters. These terrible things couldn’t really have happened. Or could they? Are both his beloved children dead or estranged? It is hard to unravel the truth of his memories, but this is the effect of trauma on memory, and this trauma is passed to the next generation.

He and June were raised in Catholic orphanages, and both were survivors of sexual abuse. These horrors come to us in fragments. Tom feels more for his wife and ‘all the hurt children’ and underplays his own trauma, remembering it as if it had happened to other boys.

Tom’s hermit-like existence is disturbed one stormy night by two younger detectives, asking for his help with a cold case that now has been reopened with additional witnesses. In the 1970s, Tom and his partner had made a strong case of child sexual abuse against two priests. The Police Commissioner would not proceed and passed the evidence to the Catholic Church to be dealt with internally, which of course it wasn’t. One of the priests is now dead, in fact murdered. Was Tom involved? There is now enough evidence to convict the other priest and times have changed.

The darkest of Tom’s memories resurface. We learn terrible and heartbreaking truths.

This is not the only work of Irish literature to deal with the grim history of abuse and cover-up by the Catholic priesthood, but it is certainly the most powerful.